Jim van Belzen

If the sea itself were to raise our coastline, a rise in sea levels wouldn’t be such a problem. A strange thought? Coastal ecologist Jim van Belzen from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) is trying to use nature to keep the Netherlands dry.

"Can nature do our coastal defence for us?"

What are you researching?

I specialize in "estuarine biogeomorphology": how plants and animals in brackish waters, like humans, try to shape their environment. Seagrass holds sand and silt in place, preventing it from washing away. An oyster reef slows down the waves, thereby reducing the erosion of the reef and the tidal flats. For the Sea Level Rise Knowledge Program, I research how we can harness these natural processes to protect ourselves from water.

How did you get here?

I’ve taken a rather unusual route. I started with an MBO in Electrical Engineering, then studied Applied Chemistry at an HBO level, and worked in a laboratory. In the evenings, I studied Environmental and Nature Science at the Open University. For my master's thesis, I took a bold step and emailed NIOZ to see if they had anything related to my field of interest. They did. Using aerial photos of salt marshes (or "tidal flats," land covered by vegetation that is submerged at high tide), I discovered that you can tell how healthy a marsh is by looking at the patterns in the grass tussocks.

I then completed my PhD on the resilience of salt marshes: the plants strengthen the soil against storms, a marsh can regenerate itself if a section breaks off, and it grows in line with the rising sea level by trapping sand and silt.

What does your research look like?

Since 2010, I have been using computer models, aerial photos, fieldwork, and experiments to study how we can harness the resilience of salt marshes as protection against water. Strengthening and restoring dikes is expensive and requires human effort. Can nature do our coastal defence for us? In my view, this is how we apply technology in a modern way. Just as a vaccine strengthens your immune system, we should design the land with nature and smart dikes, allowing the coastline to reinforce itself.

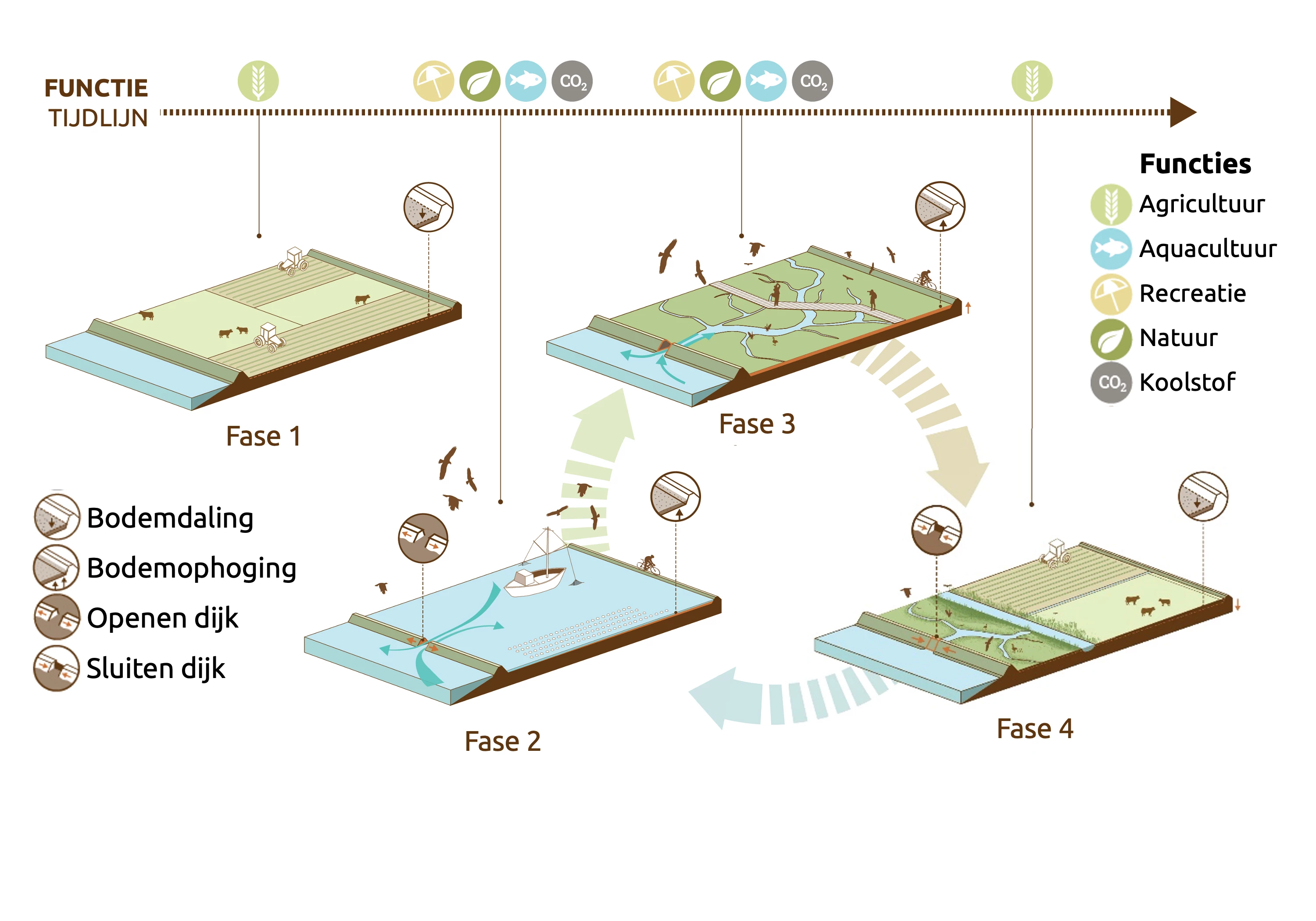

For example, with a swap polder: a piece of land between the sea dike and the dike behind it, which is gradually built up by tidal action. After 30 to 50 years, this land can rise by as much as 3 meters above sea level. During those years, it becomes a highly biodiverse area, storing carbon and breaking down nitrogen. Afterward, it can be used again for agriculture.

Why is your research important?

We face a significant challenge in keeping the Netherlands dry. The sea level is rising and the land is sinking. Relying solely on dams and dikes to solve this problem is very expensive and makes us vulnerable. A wider dike zone with swap polders inland is more robust, requiring fewer costly materials and less maintenance. The biggest challenges are the space needed and whether people will feel safe with this solution.

What do you hope to have achieved in 5 years?

In 5 years, I hope that the first pilot project with a swap polder will be a reality. The water board plans to seriously consider using swap polders for coastal defence only from 2050, but the natural processes take time. We need to start as soon as possible to avoid missing out on 25 years of sediment accumulation.

Would you like to learn more about the work of the NIOZ or Jim van Belzen?